Story by Michele Fisher • Portraits by Jody Somers View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

In 1980 the assassination of Beatles legend John Lennon and the eruption of Mount St. Helens grabbed headlines in the United States. Delivered with less fanfare was news that a virus known as human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) was identified – understandably so, as it was found to be prevalent in other parts of the world including Japan, Africa, South America and the Caribbean – not in the U.S. Known to infect T cells (a type of white blood cell), HTLV-1 is commonly transmitted through blood transfusions or breast feeding and can cause leukemia and lymphoma. Screenings for HTLV-1 in donated blood didn’t take place in the U.S. until 1988. In Jamaica those screenings started in 1989 – too late for a little girl born in that island nation four years earlier.

Now 32 years old, Sandrine Holloway-Davis recalls how she first learned she had HTLV-1. It was in February 2013 after coming out of a weeklong sedation following the emergency delivery of her first and only child at 29 weeks. It was an unbelievable result, as Holloway-Davis has always been physically active, even as a child growing up on her family’s farm in a rural, mountainous area of Jamaica. “We had a lot of land – always running up and down – always outside,” she recalls. “I always ate a lot of fresh fruit and enjoyed the fresh air. I never felt so poorly. They said pregnancy was the trigger. I learned many Jamaicans have the virus and are asymptomatic until something traumatic happens.”

When Holloway-Davis was born, she had jaundice and received a blood transfusion not knowing it contained the HTLV-1 virus that would remain dormant in her body until her pregnancy. She enjoyed good health while on the island and through her early years in the U.S., having first come to New Jersey as a student at Georgian Court University to work on her BS/MBA.

She met Henry Odell Davis III – ‘Odell’ as he is called by most – a professional musician who played at the university’s annual gala. They met via Facebook “when it was only for college students,” she notes. He was attending school at the time for a degree in computer science. Their mutual friends on social media let her know Odell was a “very nice guy.” The two hit it off, and as they journeyed into life as a newly married couple, they settled in Oakhurst near the shore in Monmouth County given Holloway-Davis’ love of the beach. What they didn’t know at the time was three years into their marriage they would face the biggest test of their lives.

“I love the beach. I always dreamed about going to play with my child outside,” shares self-proclaimed “island girl” and Jamaica native Sandrine Holloway-Davis, pictured with husband Odell and daughter Arya.

Bittersweet Challenge

While ecstatic about finally expanding their family, “I didn’t think pregnancy was for me,” Holloway-Davis recalls about how poorly she felt heading into 2013. She didn’t want to risk having a lot of tests and just wanted to “at least get the baby to 30 weeks.” She was willing to endure whatever was necessary “and whatever was wrong with me, we could fix after.” On the day of Super Bowl 2013, Odell returned from playing out of town. His mother stayed with Holloway-Davis in his absence. After hardly eating and being in a severely weakened state, this mother-to-be was taken to the emergency room at Monmouth Medical Center (an RWJBarnabas Health facility).

At first it was thought she simply needed fluids, but after further assessment the doctors “took off like wildfire, and it was a race against the clock,” she recalls being told. On the next day, which was their anniversary, Odell was told by the medical team that “we can save your wife, save your child, or try to save them both.” The decision was obvious to this young husband – try to save them both. “I was told he went to the bathroom and prayed and cried. I call him ‘Samsonian’ (referring to the biblical man of strength). I don’t know how I could have endured this without him,” reflects Holloway-Davis.

Sedated, she was soon rushed in for an emergency cesarean section. She delivered her little girl, Arya, at 29 weeks and five days – just shy of the 30 weeks she was hoping to reach. Despite weighing only 2 pounds and 13 ounces, the baby was fine and placed in the neonatal intensive care unit at Monmouth Medical Center. A week later, Holloway-Davis came to, not even remembering she was pregnant until she felt the incision in her pelvic area. Knowing that Arya was in good hands and her husband was there every day playing gospel music and reading to both mother and baby, Holloway-Davis knew she would be okay.

She finally learned of the origins of HTLV-1 from her doctor, and they talked about next steps: chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant from another donor (allogeneic). “At that point, I didn’t care about where it came from. I just wanted to know what to do to get rid of it,” recalls Holloway-Davis.

She was soon released and underwent six cycles of chemotherapy and had her marrow tested for a transplant. Luckily, she was a candidate. “I thought ‘good, this is over.’” But it was only the beginning. The task was on to find a match for the transplant and the center that would manage this unique procedure and post care. Given a recommendation of a center in northern New Jersey, one in Manhattan or Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in the central part of the state, the choice was easy.

Meeting a Mensch

Her doctor told her about Roger Strair, MD, PhD, chief of the Division of Blood Disorders at Rutgers Cancer Institute, and the expertise of the Hematologic Malignancies Program and Blood and Marrow Transplant Program teams that work in concert with one another at Rutgers Cancer Institute and its flagship hospital Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital on the RWJBarnabas Health campus in New Brunswick. “He told me Dr. Strair is a ‘mensch.’ I never heard that word before,” Holloway-Davis shares. But after meeting Dr. Strair in July 2013, she quickly learned how that endearing term exactly described this consummate professional and all around ‘good guy.’

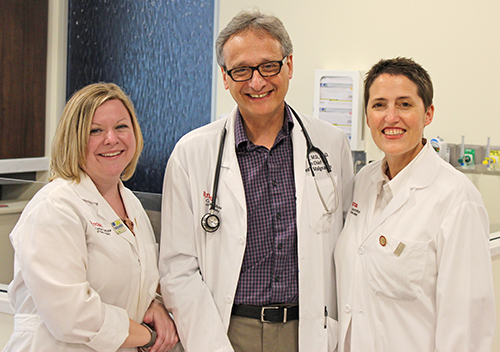

From left: Mary Kate McGrath, MSN, RN, APN-C, OCN, BMTCN, Roger Strair, MD, PhD and Jackie Manago, RN, BSN, BMTCN are part of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program team that cared for Sandrine Holloway-Davis.

“Mrs. Holloway-Davis’ case is unique to say the least,” notes Strair, who is also a professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “When she arrived at Rutgers Cancer Institute, she presented with a lymphoma that is associated with the HTLV-1 virus. Only a small percentage of patients infected with the virus ever develop lymphoma. Over the 20 plus years I have been at Rutgers Cancer Institute, our team has managed about 20 cases of HTLV-1 associated lymphoma.”

As with any bone marrow transplant “finding a match can be challenging,” shares transplant coordinator Jackie Manago, RN, BSN, BMTCN as a number of donor genetic features need to be as identical as possible. Manago also points out that “identifying a match for those of Caribbean descent can be problematic in part as there is a great genetic heterogeneity spread amongst a relatively small population.” “They were very honest with me,” Holloway-Davis recalls. “They made no promises about finding a match.” But in two weeks, an acceptable candidate was found.

The Big Blast

Still fatigued from her initial chemotherapy regimen, her immune system was at risk. “I remember the doctors telling me that I needed to be careful. I couldn’t receive flowers – couldn’t change my daughter’s diaper. I thought ‘What kind of mother am I going to be if I can’t even change my child’s diaper?’” But Holloway-Davis didn’t let any negativity creep in. Her family stepped in to help and she concentrated on getting well.

Next was the transplant chemotherapy – “the big blast,” as she calls it – to rid the body of any remaining cancer cells and prepare the body to receive the donated marrow. The self-proclaimed “island girl” feeling “blessed and ready to fight” came upon part of the process that presented a challenge. “During the orientation I was told I could not be in the direct sun (following the transplant) – that hit me. Losing my hair? Didn’t matter. Graft-versus-host disease? Didn’t bother me. But I love the beach. I always dreamed about going to play with my child outside.” Holloway-Davis made sure to address that concern by wearing 100 SPF sunscreen and a large hat whenever outdoors.

The transplant itself (a procedure similar to giving/receiving blood) was uneventful. But another downside to the process was the 30-day inpatient, post-transplant regimen. She had acute graft-versus-host disease – a common transplant complication in which the new immune system from the donor cells attacks parts of the host body – but she recovered. The toughest part during that post-transplant hospital stay was that Arya, who just turned 6 months old, wasn’t permitted to come in her room – 30 days of not holding her baby girl. “I would just look at her and Odell through the little window of the door in the Bone Marrow Transplant Unit. Sometimes I had a mask on (to protect her from germs). I was hoping Arya would at least remember my eyes.”

Unfortunately within six months she had a recurrence. Strair felt Holloway-Davis would benefit from another transplant. “It is very rare to receive a second transplant after the disease relapses following an initial transplant,” notes the doctor. The same marrow previously collected was used, but Holloway-Davis had to endure “the big blast” again. Holloway-Davis wasn’t rattled.

“I trusted them (Strair and team). I trusted them through and through. I knew from the beginning they weren’t going to sugar coat anything, and they would tell me things as they were. I appreciated that, because I was able to mentally prepare for whatever might come. Hope for the best – prepare for the worst,” she confidently shares. Arya was approaching her first birthday, and after undergoing the second transplant it was another period without her in her arms – but worth the wait. Despite the challenges of the past several months, Odell had finally finished his degree. “Three months after my second transplant, I went to his graduation bald as ever but happy as ever with Arya at my side,” she says proudly.

Sandrine Holloway-Davis

The 5 F’s

Strong in her faith, she recalls writing “Strong Faith = Strong Finish” on her white board in the hospital room. She kept it there as inspiration during her times in the transplant unit, knowing that her family, friends and community were praying for her.

During one of her post-transplant stays, Holloway-Davis was craving some dishes native to her homeland. A family in the area with close Jamaican ties learned she was in the transplant unit and came calling most evenings with home-cooked meals and great conversation. “I was so appreciative, I could cry.”

Faith, family, friends, food, “and fun,” chuckles Holloway-Davis, who is very eager to point out the positives of the experience – the five Fs. “My room was the ‘party room’ with some form of entertainment. Some days I would put on my iPod and walk up and down the hall with my ‘side kick’ (her mobile intravenous pole) and get my exercise playing high-energy gospel music. Everyone would just look at me and laugh!” Keeping in good spirits, she would take pictures of whatever was hanging from her “side kick” and post them to social media labeling the “platelets as pineapple juice, the stem cells as guava juice and the blood as sorrel – a Jamaican holiday favorite!”

But the best medicine has been her little girl – “Dr. Davis,” this mother says proudly. Told that depression could be a treatment side effect, Holloway-Davis says “not a chance with Arya around. She gets out her toy doctor bag. We bought her a real pink stethoscope. ‘Mommy, stick out your tongue, take a deep breath.’ It’s a riot. I can’t wait until she’s older so I can tell her all that has happened and have her understand the contribution she made to my healing. It’s incredible.” And at 4 years old, Arya “has not yet been tested for HTLV-1,” notes mom, but knowing her own journey, it is definitely on the family’s radar.

“I don’t know when remission happened,” adds Holloway-Davis, “it just happened,” although she says it’s been a little more than a year. Taking 17 medications a day, she follows up with Strair and his team once a month for now. Like the “soldier” her father raised her to be, she battles treatment complications like cataracts caused by steroids that help manage graft-versus-host disease.

She notes emotional and mental challenges too. But she’s pushing toward that “strong finish” and a day when she can share with Arya the lessons she learned through this experience and the values she holds dear: “a positive attitude, kindness, generosity, support, gratitude and ownership – because at the end of the day, you’re responsible for your own health.” With that, she notes she’s grounded here with her family and extended family of Strair and team, “Odell gets job offers from as far away as California. He politely declines, saying ‘No, my wife’s doctors are here. We’re not leaving.’” ■