Story by Michele Fisher • Photos by Nick Romanenko View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

At 28-years-old, Rachael McCleery never thought she would be battling a second bout of ovarian cancer. Advances in precision medicine at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey are giving her renewed hope.

The smile on her face and beaming attitude didn’t look like they belonged to someone experiencing a second bout of ovarian cancer – especially someone who is only 28. But those who know Rachael McCleery know her positive exuberance is a constant. Whether hanging out with family and friends or even being sidelined at the hospital, this is a young woman who squeezes every minute out of every day. At the time of our meeting, McCleery was taking care of some last minute blood work so that she could hop a plane the next day to visit her aunt and uncle on their farm in South Carolina. This was after she and her mom Sue told me about the recent night out on the town in Atlantic City they had for the 21st birthday of McCleery’s sister – complete with drinks, dancing and a limo. That evening was right up there with her swimming with dolphins this past summer on a family vacation to Florida.

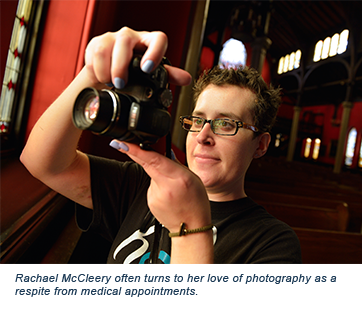

WIt was on a family vacation in 2008 at age 20 that a persistent pain in her hip wouldn’t subside. Further testing revealed two tumors, one the size of a basketball on her right ovary and one the size of a grapefruit on the left and a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. While shocking to hear in relation to her young daughter, it’s a diagnosis that mom Sue is quite familiar with, as her own mother and three of her cousins also battled the disease. Interestingly, the younger McCleery tested negative for the mutation in the BRCA genes that put one at a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer. The diagnosis was equally shocking – and devastating – to this young adult. “I was studying photography in college. I felt that my life was just starting,” says McCleery.

WIt was on a family vacation in 2008 at age 20 that a persistent pain in her hip wouldn’t subside. Further testing revealed two tumors, one the size of a basketball on her right ovary and one the size of a grapefruit on the left and a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. While shocking to hear in relation to her young daughter, it’s a diagnosis that mom Sue is quite familiar with, as her own mother and three of her cousins also battled the disease. Interestingly, the younger McCleery tested negative for the mutation in the BRCA genes that put one at a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer. The diagnosis was equally shocking – and devastating – to this young adult. “I was studying photography in college. I felt that my life was just starting,” says McCleery.

Having received the standard of care chemotherapy drugs carboplatin and paclitaxel at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia – close to her south Jersey home – she responded well, had both ovaries removed as a preventative measure and remained in remission for five years. During a routine follow-up visit that included blood work in June 2013, she learned her CA-125 levels were up. The CA-125 protein is most commonly found in ovarian cells and serves as a ‘marker’ or indicator of ovarian cancer. Unfortunately, it was just as she was turning 26 and about to come off of her parent’s insurance policy that she learned her cancer was back. Placed on carboplatin again for a few months at a community hospital near her home, the response was not what they hoped. Local doctors wanted McCleery to go to another Philadelphia facility for advanced treatment, but the issue with the insurance required her to stay in state. Not knowing where else to turn, the family called upon the surgeon who operated on McCleery a few years earlier. He and his nurse navigator recommended Dr. Lorna Rodriguez at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Out of the Box

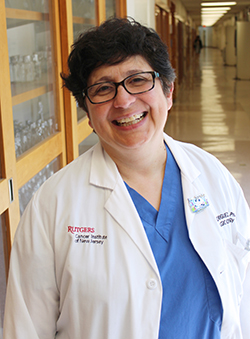

Lorna Rodriguez, MD, PhD, is the former chief of gynecologic oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute, who specializes in ovarian and other female reproductive cancers. She is also the director of the precision medicine program at Rutgers Cancer Institute. The blending of such expertise is exactly what McCleery needed at that moment. “When I first saw Rachael in January of 2014, I wanted to have her tumor genetically profiled. At that time our clinical trial examining that approach was not open, and after many discussions with both Rachael and her family we decided to perform surgery,” recalls Dr. Rodriguez, who is also a professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Lorna Rodriguez, MD, PhD, is the former chief of gynecologic oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute, who specializes in ovarian and other female reproductive cancers. She is also the director of the precision medicine program at Rutgers Cancer Institute. The blending of such expertise is exactly what McCleery needed at that moment. “When I first saw Rachael in January of 2014, I wanted to have her tumor genetically profiled. At that time our clinical trial examining that approach was not open, and after many discussions with both Rachael and her family we decided to perform surgery,” recalls Dr. Rodriguez, who is also a professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

“Dr. Rodriguez had many options prepared. She gave us hope and a new outlook on the whole thing. She was optimistic and helped restore my fighting spirit,” says McCleery, who observed that “Dr. Rodriguez has her own uplifting spirit.” “As soon as we met Dr. Rodriguez, we knew we were in the right place,” adds McCleery’s mom. “With Rachael, we need to think out of the box.” “Out of the box” is exactly what Rodriguez had in mind. Because McCleery’s cancer was slow growing, the surgery was scheduled at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJ) – the flagship hospital of Rutgers Cancer Institute – where Rodriguez removed her uterus and obtained a biopsy sample.

It was after that time that a unique clinical trial at Rutgers Cancer Institute had re-opened to accept additional patients. The trial examines tissue samples of those with rare forms of cancer and those whose cancer has stopped responding to traditional treatment. The trial is part of the Rutgers Cancer Institute’s precision medicine program. Precision medicine is an effort that drills down to the molecular level of cancer to identify changes or mutations in cancer genes that can be targeted with particular drugs. Many times, the agents identified are not traditionally used for the type of cancer presented by the patient. For instance, a patient may have a diagnosis of lung cancer, but a particular genetic change may indicate that a drug used for a different type of cancer would work better. “It’s personalizing cancer treatment,” says the doctor. Rodriguez thought McCleery might benefit from this new clinical trial.

Identifying genetic changes or mutations is done through a process called genomic sequencing, for which 200 or more known abnormalities are being screened. So far, out of more than 500 patient samples from Rutgers Cancer Institute, investigators are finding an average of three mutations in each biopsy. “When traditional care is no longer working, having three additional targets to work with helps the odds of finding an effective therapy,” offers Rodriguez. A collective of experts including medical/surgical/radiation oncologists, pathologists, basic scientists, systems biologists and others, known as a tumor board, further investigates those mutations and determines if existing agents or even investigational therapies as part of a clinical trial might help.

Exploring the Unknown

When McCleery’s biopsy came back, no mutations were found, but “variants of an unknown significance” were present. “It was a convoluted pathway to navigate,” notes Rodriguez, but after examining the results closely and drawing on three decades of her own research experience, she was able to identify a suitable drug for McCleery – trametinib – an agent known as an MEK inhibitor that blocks certain enzymes found to be overactive in some forms of cancer. The drug is currently used in the treatment of melanoma. Some patients may be apprehensive of participating in a clinical trial, but not McCleery. “It was nice to know there were other aspects available, but Dr. Rodriguez made me feel comfortable in participating.”

Taking a trametinib pill every day, McCleery’s cancer was responding well, notes Rodriguez, as most of her tumors were getting smaller. One, however, continued to grow. Thinking this tumor may be different than the others, Rodriguez prepared McCleery for a second surgery so that a new biopsy sample could be obtained. It also became clear around that time that while most of McCleery’s tumors were responding favorably to the medication, side effects were becoming an extreme discomfort. Rodriguez scaled back the medication considerably and performed the surgery at RWJ this past February (2015). Following sequencing of the second biopsy sample, Rodriguez determined that trametinib was still the optimal treatment for McCleery, but given her side-effect reaction, Rodriguez lowered the dose and altered the frequency, hoping to build her up over time to the amount of drug she was initially taking. Along with balancing the need for the medication with the side effects, Rodriguez notes another major challenge. “Some tumors learn to bypass these drugs. The plan is we continue to biopsy and figure out a new pathway and how to proceed from there.”

Slight Detour

Continuing on trametinib since the second surgery, it was in May 2015 that McCleery visited Florida. The trip was a special one, as most of her family came along, including 11 cousins – and there was a plan for McCleery to fulfill a desire to swim with dolphins. But a bout of nausea and vomiting uncovering a bowel obstruction landed her in a local hospital there. Not knowing McCleery’s medical history or current treatment regimen, the medical team at the Florida hospital viewed her scans and began an ‘end of life’ conversation with her. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. That was out of the question,” says McCleery. “All I wanted to do was get out of there and swim with the dolphins!” A quick call from Rodriguez to the medical staff in Florida with instruction to boost McCleery’s trametinib intake until returning home from her vacation, resulted in her release from the Florida hospital. She was able to finish her vacation – dolphin swim included.

Continuing on trametinib since the second surgery, it was in May 2015 that McCleery visited Florida. The trip was a special one, as most of her family came along, including 11 cousins – and there was a plan for McCleery to fulfill a desire to swim with dolphins. But a bout of nausea and vomiting uncovering a bowel obstruction landed her in a local hospital there. Not knowing McCleery’s medical history or current treatment regimen, the medical team at the Florida hospital viewed her scans and began an ‘end of life’ conversation with her. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. That was out of the question,” says McCleery. “All I wanted to do was get out of there and swim with the dolphins!” A quick call from Rodriguez to the medical staff in Florida with instruction to boost McCleery’s trametinib intake until returning home from her vacation, resulted in her release from the Florida hospital. She was able to finish her vacation – dolphin swim included.

Traveling and keeping up with her photography (photographing landscapes and the occasional celebration for friends) is what helps McCleery escape from the reality of treatments and doctor visits. And it’s the kindness of others, including many strangers, that fuels her desire to remain positive. “We have ‘Team Rachael,’” says her mom – a network of family, friends and their entire community of Barrington, New Jersey. “They hold walks for Rachael, parades and have even decorated the town fire truck in teal lights (the color of ovarian cancer awareness) for the holidays in honor of her. The whole town knows her and is in her corner.” Mom has taken all the t-shirts designed for the events held for McCleery and had a quilt created as a recent birthday gift. In the hospital or on treatment days, it provides a sense of warmth and security. But on the day of our photo shoot for this story, McCleery donned the blanket as a cape – much like a superhero – showing her strength in battling her disease and keeping close to her heart all of those who are providing support for her in her journey.

Having come off trametinib in July 2015 and placed on a traditional treatment of doxorubicin thereafter, she continues to project an upbeat attitude and attributes her joy and resilience to her faith and her vast support system, including Rutgers Cancer Institute’s entire gynecologic-oncology healthcare team and RWJ nurses, the collective that she dubs “The Dream Team.” Her advice to others walking a similar path: “Try to find the positive in everything. It’s not easy, but if you’re able to do that, you can conquer anything.”

Whatever awaits McCleery in the future, she knows that her response to the trametinib treatment for her ovarian cancer is helping to break new ground and contributing to a growing arsenal of therapies that are being found to treat multiple cancers. While she is not the first ovarian cancer patient to be treated with trametinib, her positive response gives researchers the proof they need to move forward with wide-scale testing of the agent. “Other scientists are coming to similar conclusions about trametinib and its effectiveness against ovarian cancer, but without precision medicine, we wouldn’t have known how to treat Rachael, as there was no clinical trial available exploring trametinib for ovarian cancer,” says Rodriguez. That will change, as a cooperative group clinical trial examining trametinib in ovarian cancer will open soon at Rutgers Cancer Institute, where Rodriguez and her team already know the possibilities – thanks to fine tuning of precision medicine. ■