Story by Michele Fisher • Photos by Nick Romanenko View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

At 15, Keith Pasichow was enjoying the regular, everyday activities that a teenage boy should be at that age: going to summer camp, engaging in theater arts, hanging out with friends. But six months of aches and pains in his left leg eventually led to unusual swelling in his thigh, thus beginning a journey with cancer that would later encourage a profession in which he helps children and teens traveling that same path.

At 15, Keith Pasichow was enjoying the regular, everyday activities that a teenage boy should be at that age: going to summer camp, engaging in theater arts, hanging out with friends. But six months of aches and pains in his left leg eventually led to unusual swelling in his thigh, thus beginning a journey with cancer that would later encourage a profession in which he helps children and teens traveling that same path.

After seeing his pediatrician and a number of specialists to investigate the swelling, he was diagnosed with osteogenic sarcoma (bone cancer) and referred to Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey for chemotherapy, which was followed by surgery to remove the tumor at University Hospital in Newark. Depending on the response of the tumor to the chemotherapy and the ability of the surgeon to save enough of the bone and muscles in his thigh, there was a possibility that his leg might have to be removed – but surgeons wouldn’t know that until they started the procedure. The outcome of that surgery is what gave Pasichow a positive mindset moving forward. “I knew I would have other procedures and treatment to get through, but when I woke up and realized how well the surgery had gone, I knew I would be okay,” he says.

During that first year, a clinical trial was part of Pasichow’s chemotherapy regimen. It examined an investigational drug called MTPPE when combined with the standard-of-care mix of doxorubicin, cisplatin and methotrexate. Side effects including fever were significant. “There was one time his temperature spiked incredibly high,” recalls Pasichow’s doctor, Richard Drachtman, MD, who was a young attending physician at the time and is now the interim chief of pediatric hematology/oncology at the Cancer Institute of New Jersey. “Despite how terrible the treatment made him feel, he understood he was doing a positive thing for research, even at the age of 15.”

Once chemotherapy ended, it was almost as if a shield was removed. “Patients often feel that chemotherapy is an umbrella – an extra layer that helps protect the body from the cancer – so it’s easy to feel vulnerable once it stops. After that, everyday ailments like fever and the common cold made me feel nervous, as we didn’t know if that was an indicator of the cancer coming back – but it never did,” says Pasichow.

A Beacon of Light

How have things changed since 1996 when 15-year-old Keith Pasichow was diagnosed with bone cancer? For one thing, the management of side effects and supportive care for pediatric cancer patients has markedly improved, says Richard Drachtman, MD, interim chief of pediatric hematology/oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, noting a program like LITE (Long-term, Information, Treatment effects and Evalu-

ation) is the missing piece.

How have things changed since 1996 when 15-year-old Keith Pasichow was diagnosed with bone cancer? For one thing, the management of side effects and supportive care for pediatric cancer patients has markedly improved, says Richard Drachtman, MD, interim chief of pediatric hematology/oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, noting a program like LITE (Long-term, Information, Treatment effects and Evalu-

ation) is the missing piece.

“Treatment late effects for pediatric patients are different than those experienced by adult patients, because children and teens are still growing,” notes Dr. Drachtman. That is why pediatric hematologist/oncologist Margaret Masterson, MD, and pediatric advanced practice nurse, Dawn Carey, RN, MSN, APN, created LITE, having recognized these needs.

“These are patients who could very well develop heart, kidney, neurological and other problems as they grow older due to the life-saving cancer treatment they received,” says Dr. Masterson, who is the program’s medical director and an associate professor of pediatrics at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “It is our aim to educate them about medical challenges they may face in the future and to teach them about the importance of follow-up tests and care,” she adds. Teens and young adults who are two years beyond their last treatment with no evidence of disease are encouraged to attend the program, where they are evaluated and provided with information and referrals to other specialists if needed.

The program also addresses other factors that may be problematic for this population. “Some patients have issues with health insurance, as perhaps they no longer are on a parent’s policy but do not yet have their own. We explore this aspect with them, as well as what their rights are in informing a prospective employer of their disease, and what fertility challenges they might face in starting a family one day,” says Carey, who is the program’s coordinator. “In providing younger patients with these specific resources and tools, we are helping them meet some of the most important needs of cancer survivorship,” she continues. Having experienced the LITE Program as a patient and now seeing the value of it as a physician who treats pediatric cancer patients, Pasichow says he couldn’t agree more. ■

Even though there was no recurrence, Pasichow did have his share of setbacks. Two years after the procedure to remove the tumor, surgeons had to go back in to transplant the fibula (the skinny bone in the calf) and attach it to the larger femur bone in the top part of the leg in order to help it heal better. He then underwent bone grafting (a procedure taking bone from elsewhere in the body to replace missing bone) in order to further strengthen the leg.

One of his biggest concerns as an active teen was his ability to walk. Fortunately for Pasichow, he has been able to use a crutch after recovering from that first surgery without a lot of restrictions. Now, at 33, he is conscious of late effects such as heart disease, bone pain, and fertility issues that might occur in his adult life as a result of the life-saving treatments he received. To learn more, he periodically attends sessions of the LITE (Long-term, Information, Treatment effects and Evaluation) Program at the Cancer Institute, where teens and young adults treated for a pediatric cancer are evaluated and provided with support and information about the health conditions they may face later in life (see sidebar, right).

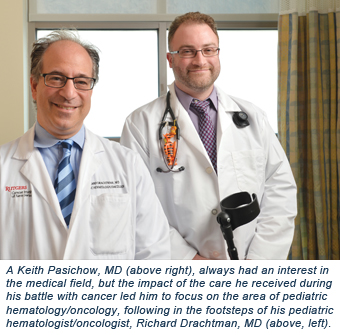

A different path of Pasichow’s cancer journey emerged toward the end of high school, when it came time to select a college. While having Dr. Drachtman’s ear as his physician, Pasichow began to have a different line of conversation with the doctor – about career aspirations. Pasichow always had an interest in the medical field, but the impact of the care he received during his battle with the disease led him to focus on the area of pediatric hematology/oncology. But another interruption of being plagued with chronic, debilitating pain during his freshman year at Muhlenberg College made him wonder if that goal would ever come to fruition. It was a slight detour that prompted a switch in majors from pre-med to theater arts, as being on multiple pain medications impacted his heavy case load in studying to be a doctor. It was a path that was meant to be, however, as in one of his theater classes he met his future wife Lisa Bracigliano who Pasichow emphasizes was, and continues to be, a major source of love and support. After a second surgery and bone grafting procedure midway through his undergrad studies, the pain subsided and it was in Pasichow’s senior year that he switched back to pre-med. He felt then that becoming “Dr. Pasichow” was more of a reality.

Fast-forward to present day and Pasichow has two more years of fellowship remaining at Columbia University Medical Center as a pediatric hematologist/oncologist. While closer to seeing his career aspirations through, it still hasn’t been easy. He remembers the very first interaction he had as a physician with a pediatric cancer patient. “It was during the patient’s diagnosis, and it felt like I was getting diagnosed all over again,” he notes. “It did take me a while to be able to separate myself from that feeling in order to better support my patients.” And when appropriate, he sometimes tells his patients and their families that he too spent time as a cancer patient. “In sharing that, I can form a connection with the patient that may be beneficial to them. And many times, parents find a sense of relief in that ‘here is someone who has been there and is now doing well.’ I can only hope to make their lives a little better during a terrible time.”

Through the years, Drachtman has been pleased to learn that some of his patients have entered the medical field – as both doctors and nurses. But having one of his “kids” follow directly in his footsteps is incredible to him. “It’s an awesome feeling to know that I did something right as a role model – that conversations we had or advice I had offered to Keith may have contributed to the career path he’s on now,” says Drachtman, who is also a professor of pediatrics at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Having celebrated five years of marriage earlier this summer, Pasichow and his wife are looking forward to a special vacation to Italy and more trips to the theater once his schedule becomes less hectic. Would he change anything about his journey? “No,” he says. “No one would choose to have cancer, but it is an experience that has made me who I am. It was horrible at times, but some really amazing things came out of it.” It is without a doubt that Pasichow’s many patients and colleagues in the field who see a bright future ahead for this doctor would agree. ■