Story by Mary Ann Littell • Portraits by John O'Boyle View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

See the full video component of Marcus' story

View more patient stories at cinj.org/patientstories

Marcus Rivera catches bad guys for a living. He’s good at it, too. He is a special agent with the Department of Justice, assigned to the Joint Terrorism Task Force, housed at the FBI. His office investigates everyone from bombers and hijackers to white-collar terrorism financiers.

He and his wife Melissa, whom he met in college, have teenage twins, a boy and a girl. “I love my work and have always felt that I was making a difference,” says Rivera, now 49. “While I didn’t specifically plan it, my education has been Jesuit, from 9th grade to grad school. The Jesuit tradition is: ‘Men for others.’ It’s what we do.”

Rivera was getting ready for work that morning in 2001 when terrorists hijacked two planes that brought down the Twin Towers—and two other planes that crashed into the Pentagon and a field in rural Pennsylvania. At the time, he was in the Office of Labor Racketeering, investigating organized crime. Running late, he’d turned on the TV to hear the traffic report. The tone of the newscast changed. “I saw that both towers had been attacked,” he recalls. Horrified, he jumped into his government-issued police car and raced to New York City.

On the West Side Highway, he saw the second tower in his rearview mirror. “I glanced back to get a better look, and the tower was gone,” he says. Black clouds of toxic dust filled the sky.

Over the next weeks and months, New York City’s law enforcement community aided in the rescue and recovery operations on ‘the Pile,’ the term first responders coined to describe the 1.8 million tons of rubble left behind by the buildings’ collapse. Rivera put in 14-hour shifts alongside his father and brother, who also worked in law enforcement. “The air smelled bad, and that smell lingered for months,” he says.

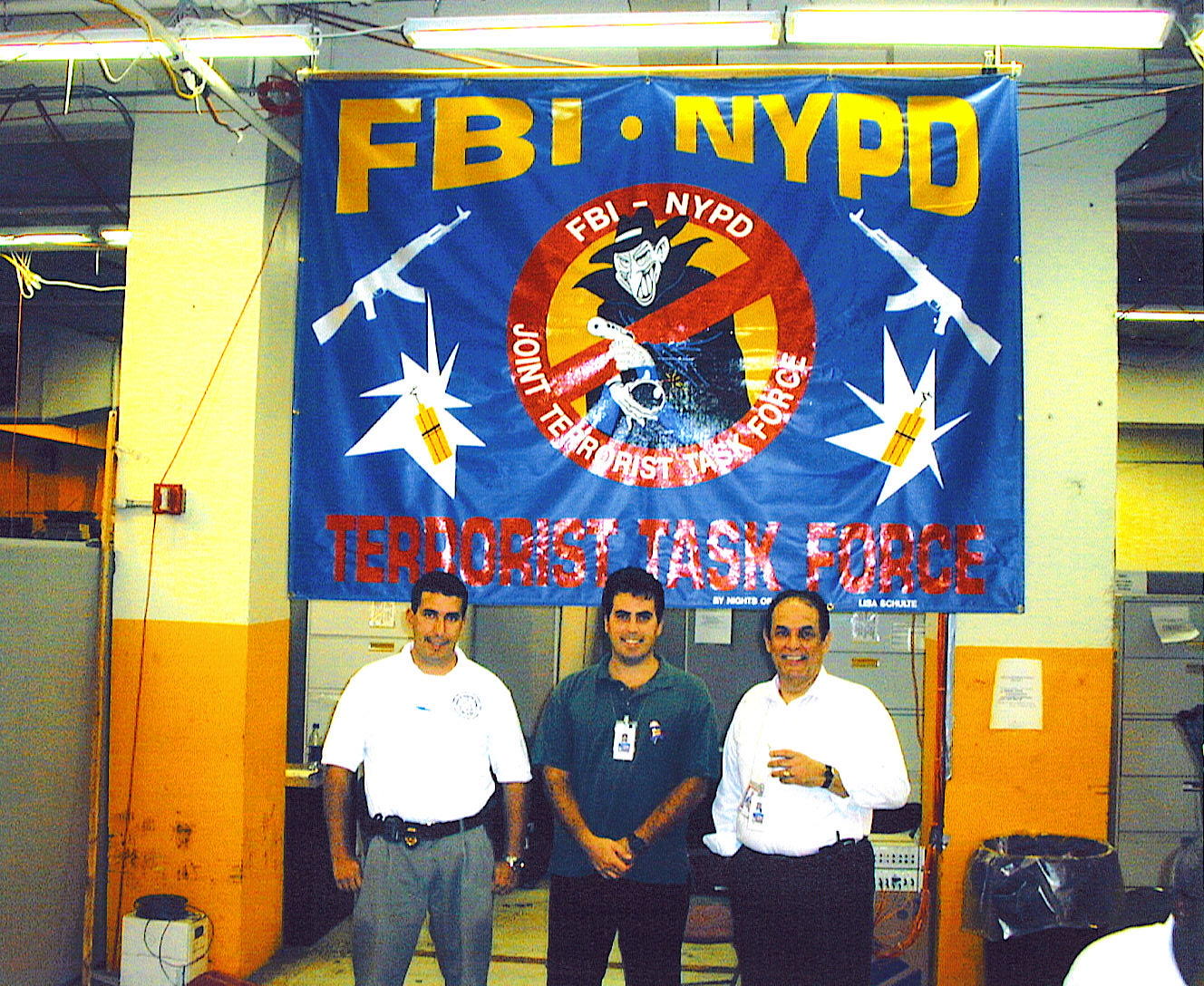

(Above Left) Marcus Rivera, his brother and his father at the temporary FBI Command Post shortly after 9/11. At the time, Rivera was a young agent assigned to the Office of Labor Racketeering, but temporarily assisting the Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) with the evidence recovery effort. His father and brother were both NYPD detectives on the JTTF. It was the only time the three worked on the same case together. The elder Rivera died at age 61 of glioblastoma, with his death being ruled ‘in the line of duty.’ (Above Right) Rivera (far left) and fellow agents searching through 9/11 debris at the Staten Island Landfill.

Returning to his regular job, Rivera worried that the time he’d spent on the Pile posed a serious health risk. He had every reason to be concerned. In 2017, he was diagnosed with a left hypoglossal schwannoma, an extremely rare tumor at the base of the skull. Though benign, these tumors can lead to nerve damage and loss of muscle control.

Some half a million people were exposed to toxic dust, chemicals and fumes in the 9/11 aftermath. With the passage of time, many became sick and died from this exposure.

Rivera is one of the fortunate ones. He was successfully treated with gamma knife radiosurgery by specialists at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital. Gamma knife is a state-of-the-art, noninvasive tool specifically designed to treat many brain conditions, including tumors and cancer.

Marcus Rivera’s care was provided by a team of specialists at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, who had great expertise in treating the rarest of tumors, both benign and malignant. “It was totally painless, and now I’m fine. I’m very grateful to these incredibly skilled doctors,” he says.

Rivera’s care was provided by a team with great expertise in treating the rarest of tumors, both benign and malignant. “They go in and ‘zap’ the tumor. It’s totally painless, and now I’m fine,” says Rivera. “I’m very grateful to these incredibly skilled doctors.”

Rivera and many other first responders are registered with the World Trade Center Health Program, a federally funded program providing no-cost monitoring and treatment of WTC-related health conditions. “I signed up as soon as I found out about it,” says Rivera. Care is provided through many Clinical Centers of Excellence (CCE), including one at the Rutgers Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences Institute. Rivera had annual checkups, first at a CCE in Manhattan, then at the Rutgers CCE. “They’re very thorough,” he states. “They watch you for symptoms of any of the known illnesses from 9/11.”

Born and raised in Harlem, New York, Rivera has been deeply impacted by the events of 9/11. In January 2006, he lost his father to glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer for which there is no cure. “He was a first responder, and it was recognized as a line-of-duty death,” notes Rivera. “It was heartbreaking—he was only 61.” A few years later, a close friend who’d spent time at Ground Zero also died from glioblastoma.

Prior to 9/11, Rivera had never heard of glioblastoma. But now he couldn’t stop thinking about it. “I became almost paranoid,” he notes. “Every time I went for an exam, I asked the doctors to check for it.”

In 2017 he began having headaches. He saw Iris Udasin, MD, director of the Rutgers WTC clinic. An MRI showed a mid-sized schwannoma. Rivera says, “When Dr. Udasin called me, the most important thing she said was: ‘This is NOT glioblastoma.’ I knew it was serious—but I was thankful that I wouldn’t have to go through what my father went through.”

Rivera was referred to neurosurgeon Steven Johnson, MD, medical director of the Gamma Knife Program at RWJUH and assistant professor of neurosurgery at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (RWJMS). “While the tumor wasn’t causing any problems now, that could change, and then it would have to be treated,” says Rivera. “Dr. Johnson said traditional brain surgery would be highly risky, but I was an excellent candidate for gamma knife treatment. I was skeptical. My feeling was, if it’s not broken, why fix it?”

In September 2021, Rivera met with Dr. Johnson’s colleague, Joseph Weiner, MD, radiation oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute and assistant professor of radiation oncology at RWJMS. The two physicians perform gamma knife radiosurgery together.

Marcus Rivera and his wife Melissa, who he describes as “my better half and always my pillar of support.”

I see many patients from the WTC registry,” says Dr. Weiner, who notes that his own mother is in the registry. A former Red Cross worker who was involved in the WTC cleanup, she receives regular checkups.

Weiner concurred with Johnson’s assessment of the tumor and the need for treatment. “The location of this tumor, on the hypoglossal nerve, impairs that side of the tongue, leading to difficulty speaking, swallowing and eating,” explains Weiner. “More serious problems may arise, including aspiration, where you could develop a serious lung infection. Also, if we waited too long, the tumor might grow, making further treatment, including surgery and radiation, even more challenging.”

Rivera decided to obtain a second opinion with the Manhattan-based neurosurgical group that treated his father and his friend. “I know them and they’re excellent doctors. I met with the head of neurosurgery,” says Rivera.

“At first, they didn’t think it was a schwannoma and suggested we watch it. Six months later, they did another MRI and said, ‘Yes, this really is a schwannoma. Kudos to the doctors at Rutgers who caught this tumor that we didn’t see.’”

That consultation was a turning point for Rivera, and he decided to go ahead. The radiosurgery was performed in December 2021 in the Gamma Knife Center at RWJUH.

Gamma knife radiosurgery is not surgery in the traditional sense. There is no incision, no bleeding, no sutures. “Gamma knife is a simple, elegant concept,” says Weiner. “A radiation source called cobalt-60 generates radiation beams that are one-tenth the thickness of a human fingernail. These highly focused beams offer very targeted radiation. It destroys the tumor, but the surrounding tissue is not harmed.”

He explains that the patient’s head is first immobilized by attaching it to a frame, or halo, with four small pins, shaped like the tip of pencil. “Once inside the machine, the patient does not move as the radiation is delivered,” says Weiner. “Instead, we move the table around. It’s quiet and not claustrophobic. Patients can listen to music, or we give them medication if they want it, so they can fall asleep. They can take a break, get up and walk around.”

For 72 minutes, Rivera listened to classic jazz as the radiation did its work. “Having the halo attached to my head was uncomfortable, but the procedure itself was easy,” says Rivera. “I felt very calm and relaxed.”

“With the gamma knife’s accuracy, the full course of radiation can be delivered in one to five treatments,” says Weiner. “For Marcus, one treatment was sufficient. He was awake the entire time, just a bit sleepy, no tubes, breathing on his own.”

(Above Left) Marcus Rivera with his halo installed, set for gamma knife treatment.

Marcus Rivera’s radiosurgery was performed in December 2021 in the Gamma Knife Center at RWJUH. Joseph Weiner, MD (above right), radiation oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute and assistant professor of radiation oncology at RWJMS, points to the benefits of treatment at Rutgers Cancer Institute saying, “Rivera saw specialists who were able to offer him other modalities. Avoiding a major surgery, he spent half a day having an outpatient procedure. It’s much easier on a patient than brain surgery. And most important, he’s had an excellent outcome.”

Once home, Rivera experienced moderate swelling at the tumor site. “It’s fairly common for the tumor to swell as it dies,” explains Weiner. “The swelling temporarily compresses that nerve, affecting the tongue. In his case, it resulted in a change in speech and tongue mobility. We gave him medication that reverses that swelling. When I last saw him, he was near 100 percent recovery.”

He adds: “The fact that he had swelling tells us that his tumor was on the verge of causing real problems, possibly waiting to paralyze his nerve irreversibly. So, our timing was good.”

After three weeks at home, Rivera was back to work. “At first I had some headaches, I think caused by the halo, but they went away, and now I’m feeling great,” he says. He will continue to be monitored through regular MRIs.

Weiner points to the benefits of treatment at a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center: “Outside of a health system like ours, this patient might have been whisked straightaway to the operating room for a major neurological surgery, which involves risks and complications, including permanent loss of nerve function, bleeding, and stroke. Instead, he saw specialists who were able to offer him other modalities. Avoiding a major surgery, he spent half a day having an outpatient procedure. It’s much easier on a patient than brain surgery. And most important, he’s had an excellent outcome. The odds are overwhelmingly in his favor that he’ll never need any other treatment for this tumor.”