Story by Mary Ann Littell • Portraits by John O'Boyle View the complete magazine | Subscribe to Cancer Connection

See the full video component of Keosha's story

View more patient stories at cinj.org/patientstories

Keosha Doyle is often asked about the deep, five-inch scar in the crook of her right arm. It isn’t pretty, but she’s not about to hide it with long sleeves.

“You’ve seen pictures of a shark bite? That’s what my scar looks like,” she says. “A chunk of my arm is gone. It used to bother me, but not anymore. It’s my battle scar—from my fight against cancer.”

For the past year Doyle has battled a cancer so unusual that it’s rarely been documented in medical journals. She struggled to find the care she needed. “First I was told that everything was fine,” she says. “When I finally knew what was wrong, the doctors I saw couldn’t help me. In the beginning I was frightened and didn’t have a lot of hope and faith that I’d get better. But as time went on, that’s what got me through.”

Keosha Doyle was encouraged by the confidence of her medical oncologist Roman Groisberg, MD, and the Melanoma and Soft Tissue Oncology Program at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

A native of New Brunswick, Doyle grew up in the shadow of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. Vaguely aware of a large medical building across the street from Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, she had no idea it was a state-of-the-art cancer facility—until she needed it.

For most of her life, cancer was the farthest thing from Doyle’s mind. This busy 27-year-old worked full-time caring for people with special needs. She attended church every week, and spent quality time with her family, with whom she’s very close.

Everything changed four years ago when she noticed a lump on her arm. It was the size of a pea and painless. “I saw two doctors and both told me not to worry; it was some sort of cyst or fatty tissue,” she states. “No one took X-rays or any other tests. I got a false sense of security.”

In the summer of 2018, Doyle had a miscarriage. In the hospital for a few days, she was alarmed to note that the lump had suddenly grown larger. The hospital staff hypothesized that it was a reaction to the medications she’d been given and advised her to have it checked out. She saw another doctor and this time had an ultrasound. The results indicated it was more than a simple cyst. “This doctor said it had some similarities to cancer, but they couldn’t say for sure that it was cancer,” says Doyle. “I was advised to see a cancer specialist.”

The mass continued to grow and was now the size of a lemon. Hard and painful, it was topped with a rash-like lesion. A local cancer surgeon removed it in a six-hour procedure and sent it for specialized testing. “When I returned to see him, the first thing he said was, ‘Is someone with you, or did you come by yourself?’ That’s when I knew I had cancer,” Doyle says soberly. “I’ll never forget that day. It was September 25, my birthday.”

"So many doctors couldn't help me," Keosha said. "But Dr. Groisberg (above) said he'd go after this very aggressively. I was ready to proceed with whatever he thought offered the best chance of a cure."

Doyle had a sarcoma, a rare kind of cancer that grows in bones, muscles, tendons, cartilage, and other connective tissue. Nearly 13,000 new cases of sarcoma are diagnosed every year in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society. Her surgeon referred her to a medical oncologist in South Jersey. “I went to see this oncologist, and he was very honest with me,” Doyle says. “He said he was not experienced in treating this type of cancer. But he knew someone who could help me. That was Dr. Groisberg.”

Medical oncologist Roman Groisberg, MD, joined the Melanoma and Soft Tissue Oncology Program at Rutgers Cancer Institute a year ago to provide treatment for patients with melanoma, sarcoma and other serious skin malignancies. With a background in molecular biology and a keen interest in early-phase clinical trials, he brings a wealth of experience in finding creative approaches to treating these complex cancers.

“Keosha had an undifferentiated round cell carcinoma with a unique genetic fusion: CIC-FOXO4,” says Dr. Groisberg, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. “It’s part of the Ewing’s family of tumors, which occur in bones or in the tissue surrounding bones. Her cancer is extremely rare. It’s the first time I’ve ever seen a tumor with this particular genetic fusion.”

Groisberg explains that in simple terms, a mistake was made when Doyle’s cells were dividing. Two genes that are supposed to be separated accidentally fused together and created a cascade of events, leading to the development of cancer. Why did the mass grow so rapidly, after four years of relative inactivity? “We really don’t know,” he says. “We don’t believe it was caused by hormonal changes related to her miscarriage or medications. As far as we know, sarcomas are not hormonally driven.”

Groisberg outlined an aggressive treatment plan for Doyle: seventeen cycles of chemotherapy, and surgery to remove malignant cells remaining at the margins. “Microscopic cells left behind—even one or two—can rear their ugly heads and grow back,” says Groisberg. “We had to remove all traces of them.”

In spite of her anxiety, Doyle was encouraged by Groisberg’s confidence. “So many doctors couldn’t help me,” she says. “But Dr. Groisberg said he’d go after this very aggressively. I was ready to proceed with whatever he thought offered the best chance of a cure.”

Groisberg is nothing if not positive, with a buoyant personality that’s reflected in his colorful bow ties. “We know that Ewing’s sarcomas respond very well to chemotherapy,” he says. “Also, patients who have chemotherapy both before and after surgery do significantly better than patients who just have surgery alone.”

In line with the Cancer Institute’s approach of treating the whole patient and not just the disease, preserving Doyle’s fertility was a high priority. “Some chemotherapy drugs stun the ovaries’ ability to function,” Groisberg says. “Ovulation usually resumes, but sometimes it does not. To preserve the ability of young female patients to have children, we first send them for fertility treatments. The ovaries are stimulated to produce more eggs, which are then frozen.”

This was welcome news for Doyle. “I worried about being able to have children someday,” she says. “I knew nothing about fertility preservation, so I was grateful to Dr. Groisberg for offering this option.” The fertility treatments were compressed into a three-week period to get her into chemotherapy more quickly.

Keosha Doyle and her mother, Yvonnetter Parkins (right).

Doyle started chemotherapy in December 2018. A combination of five drugs are given in two-week cycles. They are rotated—three drugs on one round, followed by the other two. These are strong drugs with significant side effects, so they’re given to patients in the hospital.

The first rounds were challenging. Doyle battled nausea and vomiting and lost all her hair immediately. “It was rough,” she says. “I’m sure part of it was mental. I’d have a treatment and feel sick. Then I’d go home and gradually feel better, just in time for the next treatment.” Anti-nausea medications helped, and over time her sickness abated.

“This is a compressed interval chemotherapy regimen—meaning it’s given over a shorter time span,” explains Groisberg. “It used to be given every three weeks, now it is two. We’ve found that patients can safely tolerate it, and the shorter regimen results in a significant improvement in the chances of this tumor not returning.”

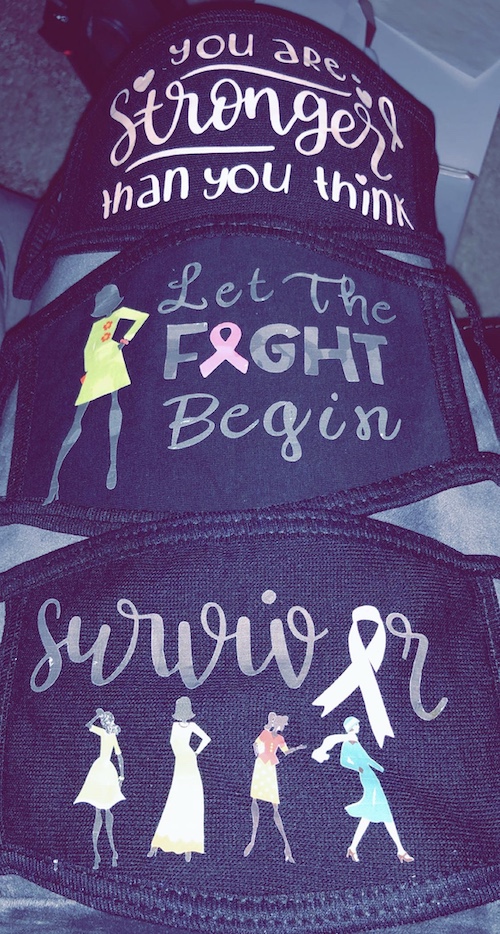

Patients undergoing chemotherapy have depressed immunity, so they are encouraged to wear surgical masks. "I hated those masks!" says Keosha Doyle. "They made me look like a sick person." So she began making her own (above). It turned into a fun little hobby and gave her "some control over the process."

Patients undergoing chemotherapy have depressed immunity, so they are encouraged to wear surgical masks when out in crowds. “I hated these masks!” says Doyle. “They made me look like a sick person.” So she began making her own. “I bought plain black masks online and got this gadget —it cuts shapes out of iron-on paper, and I could iron them onto my masks. I made one cute mask saying ‘Cancer Warrior.’ Another one said, ‘Cycle 1’ for my first round of chemo. It turned into a fun little hobby and gave me some control over the process.”

In March 2019, Doyle had surgery to remove any remaining traces of her tumor. Surgery was performed at University Hospital in Newark by orthopedic surgeon Kathleen Beebe, MD, a member of Rutgers Cancer Institute and a professor of orthopedics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, who is also affiliated with Newark Beth Israel and Saint Barnabas Medical Centers of RWJBarnabas Health. Dr. Beebe and Groisberg are frequent collaborators, meeting weekly to refer patients and plan care. “Treating sarcomas requires a multidisciplinary approach, with many different specialties working together,” says Groisberg. “Having team members at several locations helps us provide the best possible care for patients throughout New Jersey.”

Doyle’s side effects continued to improve and she was able to have her chemotherapy treatments as an outpatient, monitored closely by Groisberg and team.

“Keosha came through this process seamlessly and right on schedule,” notes Groisberg. “She’s got such incredible positive energy. It’s also a testament to the skill of our clinicians: from our advanced practice nurses, to the nurses on the floor, to the surgical team, to those administering chemotherapy in the infusion center. Everyone works in lockstep to make sure there is a good outcome for the patient.”

Her chemotherapy was finished in the fall of 2019 and Doyle is now cancer-free, with an excellent prognosis. Still regaining her strength, she’s started job-hunting. “It’s actually been fun looking for work,” she says. “I’ve been cooped up for almost a full year. Being able to get out, to get my normal life back—that feels great.”

She continues: “You always hear life is short. Now I really believe it. I’ve already been through the hardest thing I’ll ever have to deal with. If I can get through cancer, I can do anything.”

A Broad Arsenal

When facing a diagnosis of a rare melanoma, sarcoma or other soft tissue cancer like what Keosha Doyle experienced, multidisciplinary care and expertise are key.

“In the Melanoma and Soft Tissue Oncology Program at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, we work closely with colleagues across the RWJBarnabas Health system, our consortium partner Princeton University, and with other academic and industry collaborators on developing and offering the most advanced treatment options. These include immunotherapy, precision medicine, clinical trials, and complex surgical procedures,” notes Adam C. Berger, MD, FACS, (left) chief of melanoma and soft tissue surgical oncology and associate director for shared resources at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

A surgical oncologist with a specialty in melanoma and other complex skin cancers such as Merkel cell carcinoma, locally advanced basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, and eccrine carcinoma, Dr. Berger also conducts clinical outcomes research. He has been a principal investigator on vaccine clinical trials and is currently focused on examining adjuvant treatment that harnesses the body’s own defenses for patients with advanced stage melanoma.

“It’s an exciting time in the treatment of patients with melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma, because there are so many new therapies available for patients with both advanced stage and earlier stage disease. More than ever, we are now able to target therapies in a more personalized manner to better treat these two diseases and improve outcomes,” he adds.

To learn more about the Melanoma and Soft Tissue Oncology Program, visit: cinj.org/melanoma.